Part II - Lightroom Workflow

Part III - Organizing the Library

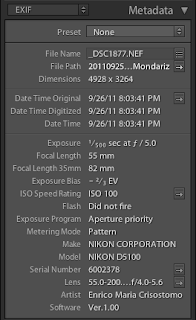

Part IV - Keywording and Metadata

Part V - Using Filters

Part VI - Importing Your Images

Part VII - Basic Editing Tools

Part VIII - Developing Your Images, The Basics

Part IX - Reading and Interpreting the Histogram - Basic Adjustments

Part X - White Balance

Part XI - The Tonal Scale

Part XII - Presence Controls

Part XIII - Coming Soon!

White Balance

White balancing an image means adjusting the relative intensities of the colors (in this case, of the three primary channels) to correct the drift. This process is usually performed over white or grey (two neutral colors).Color Temperature

When adjusting the white balance of an image, you often see the concept of color temperature. This term, borrowed from Physics, describes a characteristic of light. As much as it concerns a photographer, it's sufficient to know the following:- Color temperature is usually measured in Kelvin degrees.

- The lower its value, the warmer the color.

- The higher its value, the cooler the color.

A photographer would often know the color temperature of well known light sources, to dial into the camera the correct color temperature in advance.

If an incorrect color temperature is used, or if the camera fails in autodetecting it, the resulting colors in the image will have drifted and will appear with an incorrect hue: typically yellow or blue depending on the side of the drift. In the following picture, you can see a strongly incorrect white temperature in a shot taken indoor with a flash:

|

| Incorrectly White Balanced Photo |

In the previous picture, the temperature of a tungsten bulb (about 2800 K) has been dialed in the camera and the shot was taken indoor with a bounce flash: you can clearly see how the hues have drifted towards the blue. Now: if you're asking why it's blue and not yellow, it's just because white balance compensates the lightning conditions used to take the shot. 2800 K corresponds to a hot color (a hue towards the yellow), so the compensation is made towards the other side (the blue).

When editing RAW files, Lightroom lets you use the Kelvin color temperature scale to set the color temperature of your image, otherwise the slider will use a [-100,100] range to adjust the temperature. Fortunately, (yet) another advantage of shooting RAW is that you can correct the white balance in post-production without affecting the image nor losing any kind of information; on the other hands, adjustments on a non-RAW file are more limited and they cannot achieve the same level of accuracy that they can achieve on RAW files. This means that, although you should always try to get it right straight out of the camera, you could always go Auto and tune it in post-production.

With Lightroom you can correct the white balance of a shot using the following methods:

- You can use the color picker to sample the color of a matrix of 5x5 pixels: Lightroom corrects the white balance against the color of the chosen pixels. To use this method, you have to make sure that some neutral color is present in your shot.

- You can use a preset: Lightroom offers some presets with the temperature of many well known lightning conditions (daylight, cloudy, flash, tungsten, etc.)

- You can manually dial the color temperature.

In the following picture, you can see the relevant controls in the Basic panel:

|

| White Balance Control |

To use the first method, I could choose the color picker (on the left side of the panel) and choose some pixels on the images with neutral color. In this case, I remembered the door (where the two ribbons are hanging from) to be a pretty neutral light gray. If I sample those color, as shown in the following picture, Lightroom would choose a temperature of 5750 K that, indeed, is very close to the correct one (about 5500 K). The 200K difference in the resulting image cannot be appreciated very easily.

|

| White Balance - Color Picker to Choose a Neutral Color |

The resulting image is:

|

| Correctly Balanced Photo |

If you cannot use the color picker because your image doesn't contain any neutral color, you can balance it manually using your own judgement. The Temp slider is colored, as usually, with a hue scale from blue to yellow, as you can see in the picture of the Basic panel above. If you need to make the colors drift to blue just move the slider to the left and if you need to make the colors drift to yellow just move the slider to the right. The colored slider is a good mnemonic.

As I promised in the previous part of this series, we will check on the histogram what's going on to have a better understanding of each develop setting. In the following picture you can see the histogram of the balanced image and the picture of the unbalanced image with a -1000K compensation and a +1000K compensation:

|

| Histogram of the Balanced Image |

|

| Histogram of the Unbalanced Image (-1000K) |

|

| Histogram of the Unbalanced Image (+1000K) |

The first histogram is the histogram of the balanced image. As you can see, the three channels overlap very well on the right half of the histogram (if you recall what we've seen in the the previous post, Lightroom use the gray color where the three color channels overlap in the histogram). The corresponding pixels are those contained in the big area of the door, which is a neutral gray.

Pushing down the Temp slider adds a blue hue and we can see from the second histogram that the blue channel starts to expand to the right while the green and red channels start to compress to the left. On the other hand, when the Temp slider is pushed up and a yellow hue is added we can see that the blue channel starts to compress to the left and the green and red channels start to expand to the left.

Tint

As we've seen, the effect of changing the temperature is "shifting" (in reality, compressing or expanding) the blue channel apart from the other two channels. Intuitively you could argue that, since the relative position of the green and red channels hasn't changed so much, this process would be insufficient to correctly balance the white, at least in certain circumstances. In fact, you would be right. That's why there's another slider called Tint.The tint is an adjustment used to correct the green or magenta tint of the image. Lowering the tint value raises the green tint of the image while raising the tint value raises the magenta tint of the image. Why were green and magenta chosen? Let's return to the histogram and see what happens.

The tint adjustment has an effect on the green channel very similar to the one that the temperature adjustment has on the blue channel: it expands or compresses the green channel away from the other two:

- When the tint slider is moved to the left, the green channel expands to the right, compressing the blue and the red channels to the left.

- When the tint slider is moved to the right, the green channel compresses to the left, expanding the blue and the red channels (whose sum is magenta) to the right.

In the following pictures you can see what happens compensating the tint of the previous image:

|

| Histogram of the Unbalanced Image (Tint -20) |

|

| Histogram of the Unbalanced Image (Tint +20) |

The tint setting is seldom used, much less than the temperature setting is. However, it's important for you to know how it works since it can really help you fine tune your images when tweaking the temperature setting is insufficient. Here's an example of a picture I took recently (contrast in the mid-tones has been increased with Lightroom):

|

| Picture with a Green Cast |

Can you see the green tint in the halo around the silhouette of the building? Well, that's a green cast that must be corrected. You can see how the tint setting has been used, adding a +17 compensation, to remove the green cast from the light. The result can be seen in the following picture:

|

| Green Cast Corrected (Tint +17) |

If you want to help me keep on writing this blog, buy your Adobe Photoshop licenses at the best price on Amazon using the links below.